Halfspace: a Python package for elastic halfspace calculations

Richard Styron

(edited 4 October 2014)

Part 1: Introduction

I've been working the past year and a half on calculating topographic and tectonic stresses. This work has relied heavily on using elastic halfspace approximations, which are quite commonly used in the crustal deformation communities, particularly by geodesists. To this end, I have written a Python module for calculating the topographic stresses in a region, and for doing Bayesian inversions for tectonic stresses that lead to earthquakes. This blog post is an introduction to the use of the Python module. I am finishing up a series of IPython Notebooks that compose a tutorial of a topographic and tectonic stress inversion, using the 2013 Balochistan, Pakistan earthquake as an example. The notebooks are downloadable and executable. They are available here. But if you want to work through the examples, please clone/download the whole repo on github, which has the necessary files (DEM, slip model, and some other stuff).

The halfspace module aims to be eventually a fairly complete and modular open-source module for use by anyone, particularly by those who are not interested in coding up their own solutions (i.e. people who are not overly invested in halfspace techniques, but want to use them for a short project). Currently, though, it only has solutions for stresses resulting from surface loads (as well as a lot of utilities for dealing with stress projections and rotations, as well as other goodies). Additional solutions for strain from surface loads, as well as stress and strain from dislocations (Okada, Meade triangles, Mogi) and pressure sources (Mogi) will be added.

Introduction to the introduction

An elastic halfspace is a 'semi-infinite' elastic body; for our purposes, this means that it is infinite in the \(\pm x\), \(\pm y\), and \(+z\) directions (where \(+z\) is down). It's like an infinitely wide, infinitely deep ocean. With a flat (not spherical) surface. But elastic, not fluid.

Ok, so it's not really like an ocean. Never mind.

In any case, the 'elastic' designation basically implies all that comes with elasticity (which is less complicated than conditional or directional infinities): basically, the material instantly deforms when any stresses are applied, in a perfect Hooke's law type manner, and instantly undeforms when stress is released, so there is no time dependence here. Additionally, the material's rheologic parameters are fully specified using any two of the elastic moduli, which is convenient.

Elastic halfspaces are frequently used by geodesists and other deformation modelers because there are well-defined and usually simple mathematical formulae describing the stresses and strains that result from particular loading conditions. In the tectonics realm, this is most typically shear dislocations on a plane, simulating slip on a fault. In the volcanology realm, this is most often the opening or closing of an ellipsoidal or planar volume, simulating fluid (magma or water) movement into or out of a reservoir.

Topographic loading in a halfspace

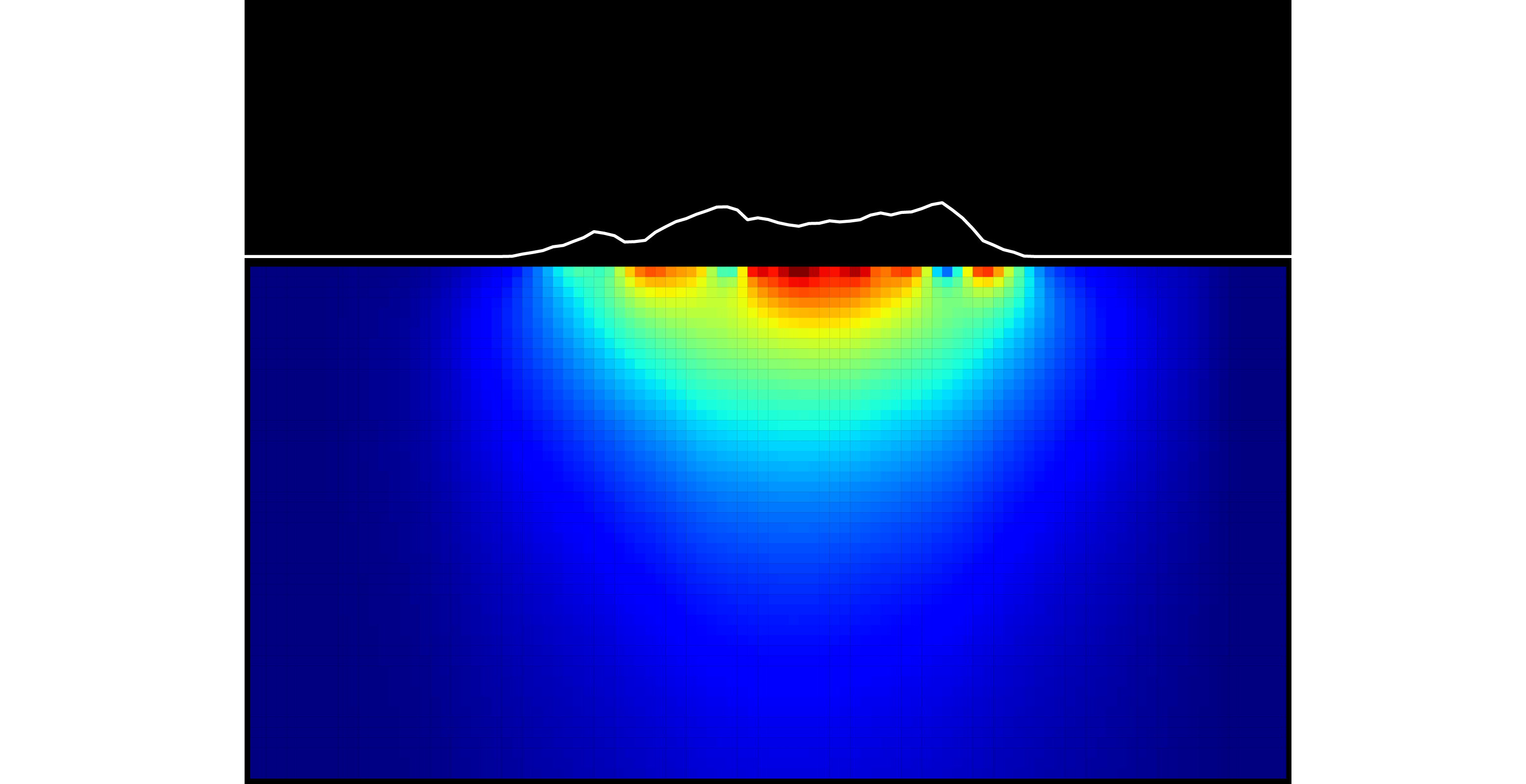

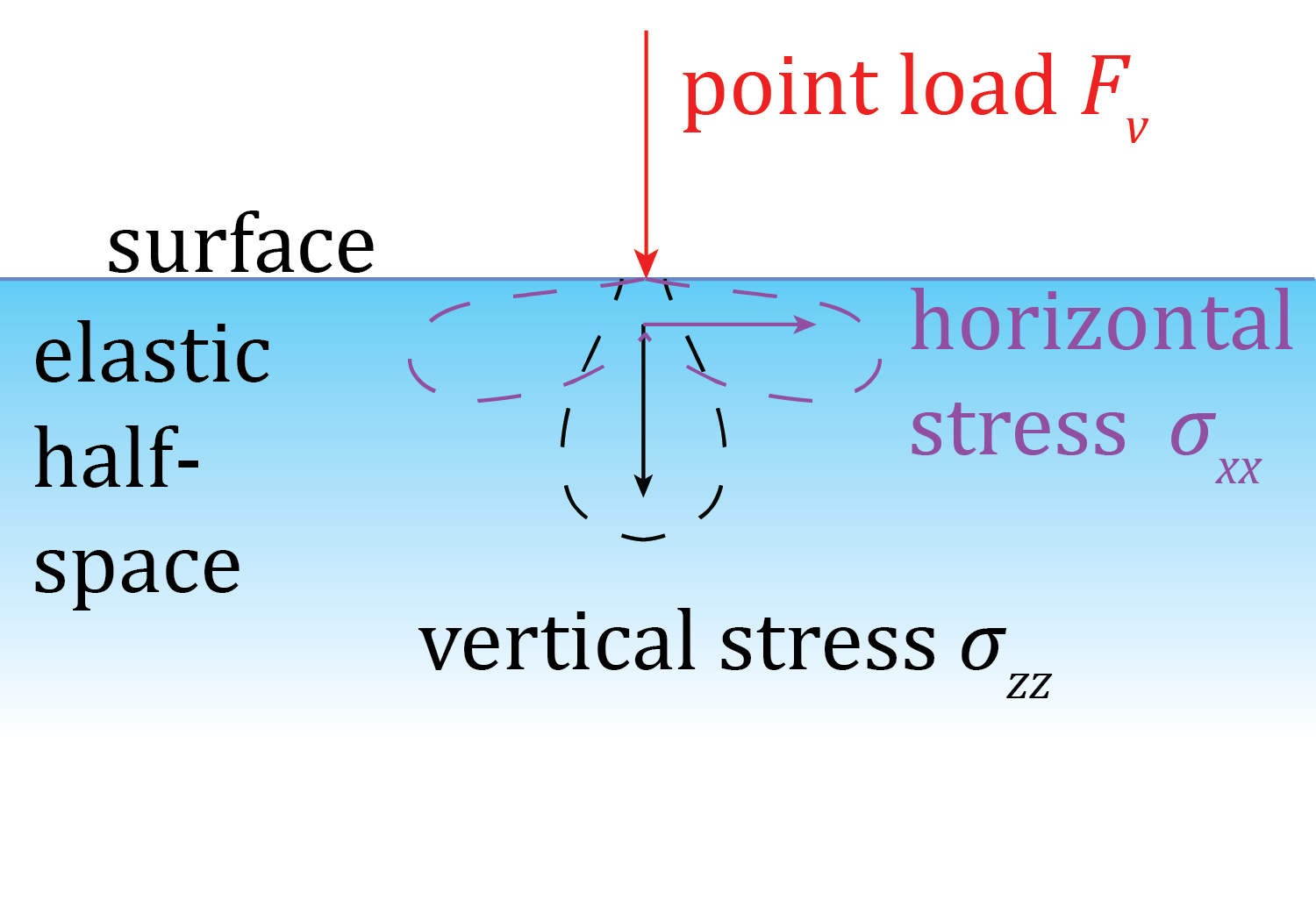

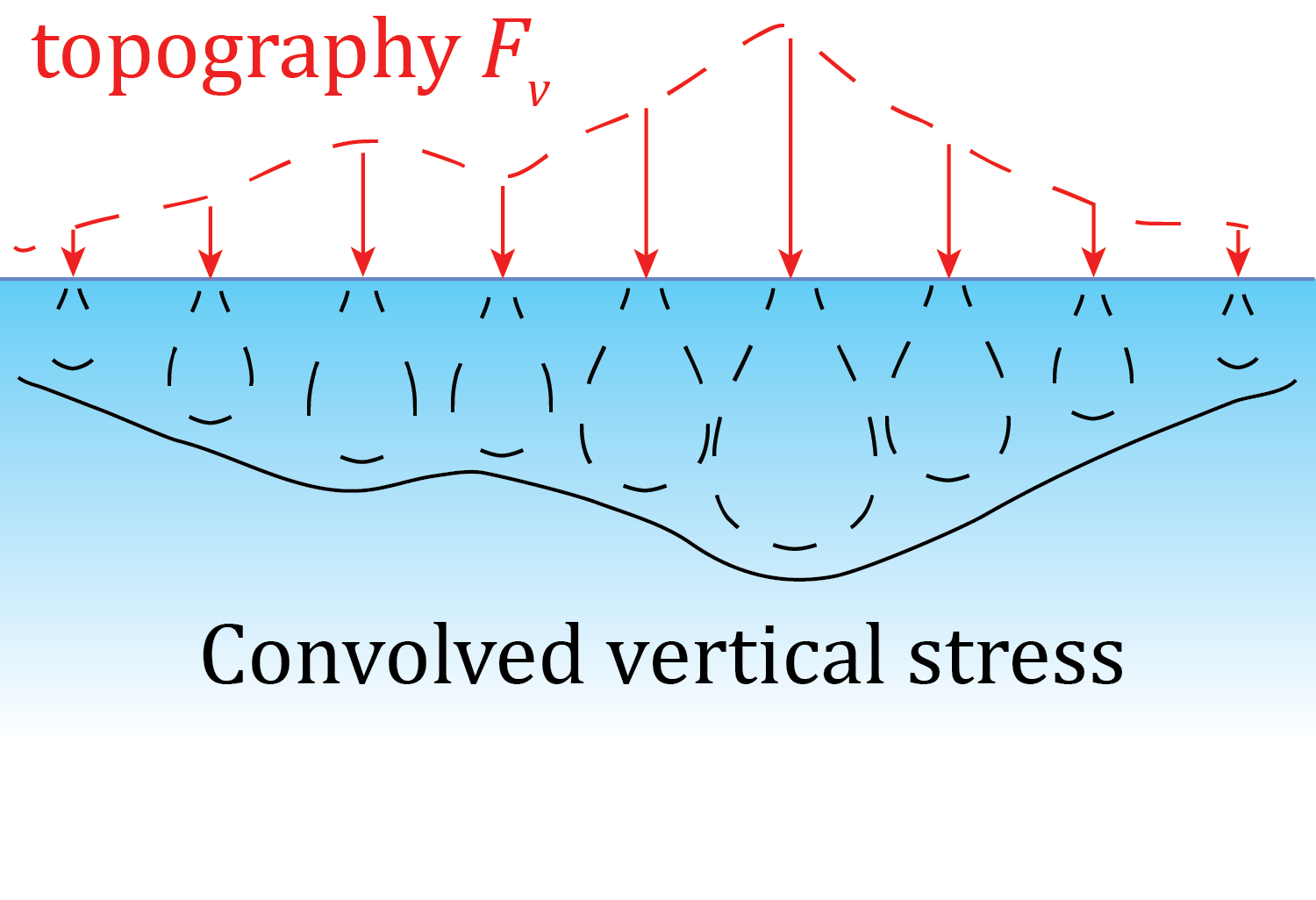

Here, we approximate stresses resulting from topography by treating the topography as basically an array of vertical point loads and then correcting for the irregular surface boundary condition, and for the shear stresses that result from slopes, by using arrays of horizontal point loads.

Stresses from vertical point loads are represented using Boussinesq's solutions, which prescribe the six components of the stress tensor at an arbitrary point from an arbitrary point load, for example:

A DEM, or digital elevation model, is basically an array of point elevations. We can use a DEM as such an array, and approximate the topographic loads by adding up the individual point load contributions:

As will be explained in the Calculating the topographic stress field section, this is done efficiently using a time-domain convolution. We'll describe that a bit more when we get there. In the mean time, we've got to get our software installed and get the data (DEM and fault coseismic slip model) prepared.

Table of contents for the rest of the guide

(Note that these may not be uploaded yet. The guides are procedurally complete, but I want to add some of the math/theory explaining what is going on as well.)

- Installation and configuration

- Preparing a Digital Elevation Model file

- Preparing the coseismic slip model

- Calculating the topographic stress field

- Calculating the topographic stresses on the fault

- Bayesian inversion of tectonic stress pt. 1: Rake inversion

- Bayesian inversion of tectonic stress pt. 2: Conditions at failure