Very short earthquake recurrence times

Richard Styron

The belief that earthquakes release most or all of the accumulated shear stress on a fault is widespread among both scientists and the general public. It is closely related to, and may stem directly from, Henry Reid's idea of elastic rebound theory: The crust slowly accumulates elastic strain until the shear stress on the fault is too great for the frictional forces resisting fault slip, and the fault slips suddenly, relieving the strain, at which point the tectonic strain begins to accumulate again, and the earthquake cycle begins anew.

Embedded in this framework for thinking about earthquakes is the idea that the probability of an earthquake occurring drops to zero immediately after an earthquake, and this probability slowly increases as tectonic stress increases, reloading the fault. Therefore, the probability of an earthquake occurring on any given section of fault is time-dependent, where time is measured as the interval since the last earthquake.

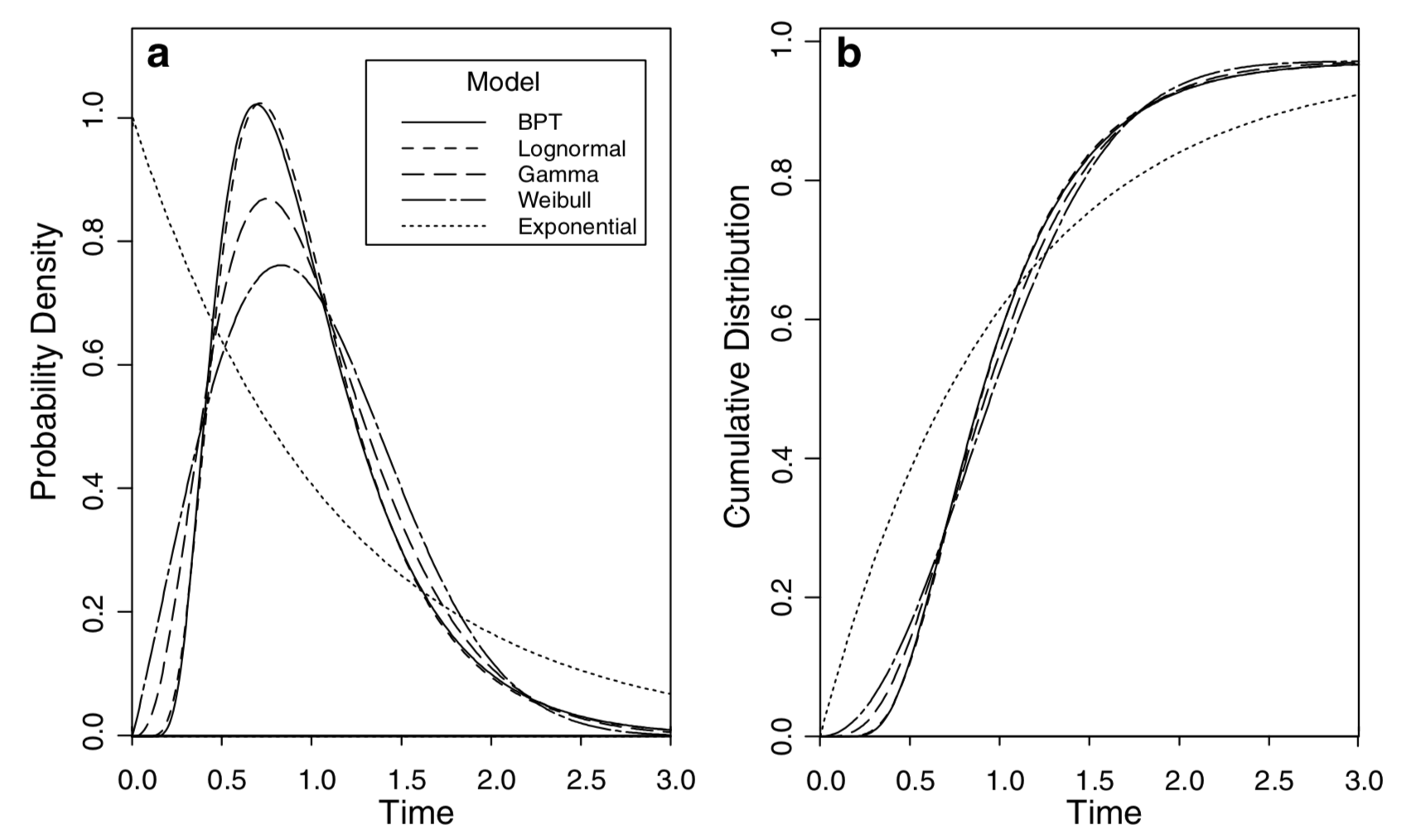

From the standpoint of earthquake probability and statistics, this means the probability distribution of the recurrence intervals \(p(t)\) is zero at time zero, i.e. \(p(0) = 0\), and \(p(t)\) is also low while \(t\) is less than half of the mean recurrence interval (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Common earthquake recurrence interval distributions, from Matthews

et al. 2002, BSSA. '1.0' on the x-axis is the mean recurrence time for each

distribution. A: Probability density functions.

B: Cumulative density functions.

Figure 1: Common earthquake recurrence interval distributions, from Matthews

et al. 2002, BSSA. '1.0' on the x-axis is the mean recurrence time for each

distribution. A: Probability density functions.

B: Cumulative density functions.

However, if earthquake recurrence is time-independent, i.e. earthquakes are randomly spaced in time on a single fault, then earthquakes are more likely to occur very closely spaced in time, and \(p(0)\) is highest that it will be, and then decays exponentially with time. (You might reasonably say, "If the earthquakes are time-independent, then shouldn't \(p(t)\) be flat?" This is intuitive but incorrect; instead, the hazard function is flat or invariant with the time since the last event. The probability of an earthquake occurring on any calendar year, not year since the last event, is also flat.)

Hazard modelers tend to use time-independent earthquake behavior for fault sources, with a few exceptions. This is generally the safest assumption as the only information required is the mean rate of earthquake occurrence, which can be estimated from a slip rates and fault dimension if the recurrence information is unknown. Time-dependent behavior requires knowledge of the mean rate, its standard deviation (or other scale parameter) and the time since the last event. These aren't known for the majority of faults.

Time-independent earthquake occurrence requires that major earthquakes on a fault don't release all of the accumulated shear stress, i.e. that dynamic friction doesn't go to zero, unless there are extremely large stress transients in the crust that are capable of reloading faults much more quickly than tectonic strain accumulation rates. These would certainly be apparent in GPS geodesy but are either not present or unrecognized.

This also applies to earthquakes that are strongly clustered in time (moreso than random). Clustered earthquake sequences are characterized by very short recurrence times separated by very long recurrence times.

Time-independent earthquake behavior and other recurrence behaviors that allow for very short recurrence intervals have very little mindshare in the geosciences outside of hazard modelers and statistical seismologists. The idea that the chances of another big earthquake on a section of fault are very low following a big earthquake is intuitive and satisfying, given both the elastic rebound hypothesis (which is surely true to some substantial degree) and the comfort given by thoughts of safety in the wake of a damaging event.

Well, is it true? I don't know, and I don't really know how to find out. I suspect that different faults or fault systems behave differently; the idea that fast-slipping plate-boundary faults are relatively periodic (i.e., time-dependent in the way discussed above) while slower, intraplate faults are random if not clustered goes back at least to Wallace, 1987.

But the big problem is that it's not easy to let the data tell us. Because mean recurrence intervals for large earthquakes are hundreds to thousands of years (or more), we don't have good instrumental data to guide us. Instead, we rely mostly on paleoseismic data. While paleoseismologists do a great job of getting this data, trenching is slow, tedious, expensive, and often ambiguous, and a good trench will typically yield evidence of a few events, with imprecise timing for the oldest events. Digging deeper is not always possible given financial, logistical or geological constraints.

My big worry, though, is that the signature of earthquakes closely spaced in time isn't recognizable in a paleoseismic trench. Check out this picture of GEM Hazard modeler and fun-haver Kendra Johnson on the Monte Vettore Fault:

Figure 2: Kendra Johnson at the Vettore Fault, October 2017. The light-colored

rock surface here is the exposed rupture surface from the 2016 Amatrice and

Norcia earthquakes. The lightest band, above her hand, shows ~20 cm slip during

the Amatrice earthquake on 24 August 2016. The ~2 m below her hand shows slip a

few months later, on 30 October 2016. Photo credit: R. Styron

Figure 2: Kendra Johnson at the Vettore Fault, October 2017. The light-colored

rock surface here is the exposed rupture surface from the 2016 Amatrice and

Norcia earthquakes. The lightest band, above her hand, shows ~20 cm slip during

the Amatrice earthquake on 24 August 2016. The ~2 m below her hand shows slip a

few months later, on 30 October 2016. Photo credit: R. Styron

This image shows distinct ruptures on the same fault plane separated by two months. Already, one year later, it's hard to distinguish between the two ruptures. It was clear in person in Fall 2017, but I don't know that it will be a year later. And this would definitely be impossible to discern in a paleoeseismic study. It wouldn't show up in a trench, nor in the cosmogenic nuclide gradients along the scarp that are used in this region for paleoseismology.

How many similar sets of events are we not recovering from an uncooperative geologic record, or from our own biases about the statistics of earthquake recurrence?

And similarly, what are we missing from individual earthquakes themselves? In a very surprising paper, Galvez et al. (2016) find that the 2011 Tohoku earthquake may have contained two successive sub-ruptures on the same fault patch. This phenomenon would be very hard to detect in much smaller (and therefore more brief) earthquakes than Tohoku.