2010 Sierra El Mayor - Cucapah Earthquake Rupture: Initial field photos and impressions

Richard Styron

This post originally appeared 29 March 2011 on my old blog. The text and figures are shown unedited.

I just returned from a short trip to the site of the M 7.2 Sierra El Mayor –

Cucapah (Baja California) earthquake that occured 4 April 2010. The

purpose of

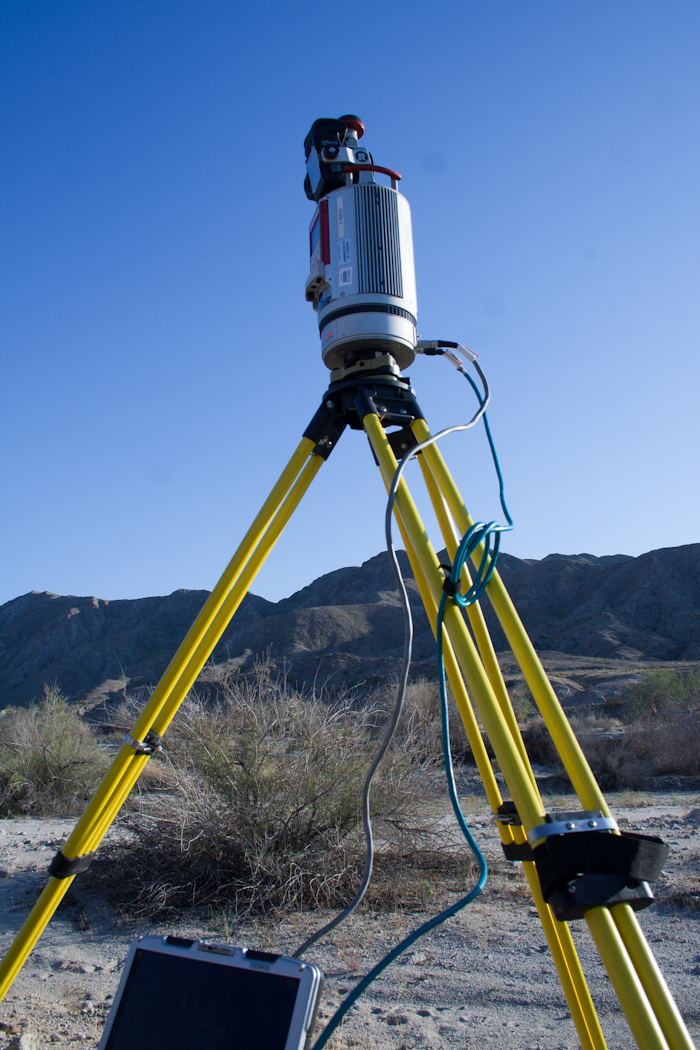

the trip was to perform a repeat Terrestrial LiDAR Scanner (TLS) survey of

selected areas of surface rupture (mostly along the Borrego fault), to quantify

changes to the scarp and surroundings over the past year. This project is a

collaboration between UC Davis (Mike Oskin, Peter Gold and

Austin Elliot),

KU (Mike Taylor, A.J. Herrs, and myself) and CICESE (Alejandro

Hinojosa). John Fletcher at CICESE seems to be the head of the non-TLS

investigations, of which there are many. It’ll be a little while until this

year’s data is processed, but here are my first observations and some photos

from the trip.

I just returned from a short trip to the site of the M 7.2 Sierra El Mayor –

Cucapah (Baja California) earthquake that occured 4 April 2010. The

purpose of

the trip was to perform a repeat Terrestrial LiDAR Scanner (TLS) survey of

selected areas of surface rupture (mostly along the Borrego fault), to quantify

changes to the scarp and surroundings over the past year. This project is a

collaboration between UC Davis (Mike Oskin, Peter Gold and

Austin Elliot),

KU (Mike Taylor, A.J. Herrs, and myself) and CICESE (Alejandro

Hinojosa). John Fletcher at CICESE seems to be the head of the non-TLS

investigations, of which there are many. It’ll be a little while until this

year’s data is processed, but here are my first observations and some photos

from the trip.

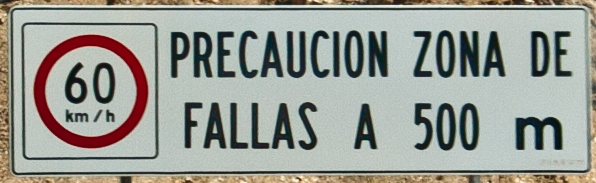

First off, the surface ruptures are pretty amazing. While they look generally similar to what I would have guessed, it was still fantastic to see the ground shattered like it was. A 2 meter cliff ripping across a landscape where none existed shortly before is a very exciting thing for someone obsessed with the earth to see. Preservation in our study area is also excellent. The Gulf of California rift valley is very dry, and fluvial surface modification is minimal: tire tracks cut by the fault scarps (i.e. a minimum of one year old) are still preserved.

These tire tracks were cut by the surface rupture. A small scarp is in the foreground; note the dextral offset in addition to the normal offset. The tracks lead straight into the main scarps, which for some reason have blocked post-earthquake traffic.

The style of surface rupture changes dramatically along strike, and seems controlled by local changes in the substrate as well as the local geometry of the rupture. Where bedrock or fairly well indurated sediments were near or at the surface, the rupture is concetrated on a small number (often one) of individual fault strands with larger displacements, and where those rocks were buried with significant thicknesses of poorly consolidated sediments, the surface displacement occures along many smaller faults. In some cases where there is a significant thickness (meters to tens of meters (?)) of sand and silt overlying stronger rocks, the displacement zone is generally diffuse and monoclinal rather than comprising discrete breaks at the surface, even though some of these are sites of maximum coseismic vertical displacement in the region. While this general trend of more concentrated faulting in more competent rock isn’t particularly surprising to me, it was still very cool to see in the field. As much as the phrase ‘natural laboratory’ is overused, this is a pretty good example of one.

Blind faulting in deep silt and sand along the western rangefront. Vertical

displacements here were the some of the highest along the Borrego rupture.

Austin Elliott is at the bast of the scarp for scale.

Blind faulting in deep silt and sand along the western rangefront. Vertical

displacements here were the some of the highest along the Borrego rupture.

Austin Elliott is at the bast of the scarp for scale.

Very discrete rupture in well-consolidated conglomerate. Top of reflector on

tripod is just over 2 m above the ground. Most if not all of the sediment on

the debris cones at the base of the scarp is from co-seismic shaking.

Very discrete rupture in well-consolidated conglomerate. Top of reflector on

tripod is just over 2 m above the ground. Most if not all of the sediment on

the debris cones at the base of the scarp is from co-seismic shaking.

The overall geometry of the rupture also controls the local degree of displacement concentration: faulting is much more distributed in step-overs in the rupture than along long, straight segments. Again, this is not at all surprising, but still great to see. There is a good range of structures accommodating step-overs: relay ramps, tension gashes, etc. These seemed a bit disorganized at first, but as I got to know the place a bit better, the method overshadowed the madness.

Relay ramps accommodating fault step-overs. Note how scarp on left dies out to

the right, and the next highest scarp picks up before dying out as well.

Although it isn't easy to photograph in the field because of vegetation, the

main rupture stepped back behind these two tilted blocks to the right of the

big bush at the right of the photo. The highest 'scarp' visible is actually a

cut bank, which is now 2 m above the present channel floor.

Relay ramps accommodating fault step-overs. Note how scarp on left dies out to

the right, and the next highest scarp picks up before dying out as well.

Although it isn't easy to photograph in the field because of vegetation, the

main rupture stepped back behind these two tilted blocks to the right of the

big bush at the right of the photo. The highest 'scarp' visible is actually a

cut bank, which is now 2 m above the present channel floor.

In general, the scarps were very steep. The focal mechanism for the event from the USGS has dextral and east-side up faulting occuring on a subvertical (dip 82 to the NE) fault. Most of the rupture shows dominantly strike-slip displacements, as well as east-side up faulting (I hesitate to call it normal or reverse because the fault is so steep), but in our field area on the Borrego fault, most of the faulting is east-side down, and the dip slip component is much greater than the strike-slip component. I haven’t wrapped my head around the change in sense of throw yet, partially because I don’t know enough about the structure of the area, but I suspect it has to do with fault interaction at depth. There could be a big slip partitioning story going on, where surface extension is accommodated on mode-I fractures that are not always part of the main scarps:

(Mostly) extensional fractures on the upthrown fault block

This will all get sorted out once we really sink our teeth into the LiDAR data, which should happen this summer. First, though, here’s a picture of the scanner:

Riegl VZ400 Terrestrial LiDAR Scanner. Towards 3 PM in the desert sun, this thing really starts to resemble a $250,000 can of Tecate.

Our field crew. From left: Octavio, Alejandro Hinojosa, Mike Taylor, Austin Elliott, myself, and Peter Gold. Note the ruptures at the base of the mountain to the right.